In the zone between

Chile and Argentina, Livermore stopped to appreciate crossing a high mountain

pass. Livermore and Dr. G had been stamped out of Chile and their motorcycles officially exported from the country.

17 kilometers away from this photograph, at Immigration for Argentina,

the pair and their motorcycles were government-wise refused entry, with three

Argentine officials signing off on the refusal document. The nice sunny day photographed here became a

dark day for a few hours until a lady succumbed to the wily ways of sweet

talking motorcyclist Dr. G.

Argentina Denied Entry, Americanized, Bidet Mouth Washer, Ozzy Osbourne

Doppelganger in Buenos Aires

Two different approaches to the bureaucrats at the immigration

offices to Argentina received two different results. Livermore was told, to go away, “Not my problem! You go

back to Chile. Cannot enter Argentina!”

Meanwhile Dr. G’s immigration official answered his question

about how big her husband was with a smile. While Livermore was flustering at

his counter with several bureaucrats, fostering his papers, passport, credit

cards and documents for his motorcycle, Dr. G was asking at his counter what

kind of dancing the female official liked.

A major problem was Livermore had wrongly assumed

a required document, called a Reciprocity Fee, could be purchased at the

border, having failed to do so where he had Internet access over the previous months. However, the fee could only be

paid online and no Internet access or Wi-Fi connections were available to travelers at the border.

The nearest was 25-30 kilometers back in Chile, so at least two days would be

lost re-entering Chile, finding an internet connection and printer for Livermore to make the

required credit card payments, securing a numerical verification and then printing proof and exiting Chile again and re-starting the Argentina

immigration and temporary vehicle import process. It had been Livermore's responsibility to pay for the required Reciprocity Fees.

The problem was solved when Dr. G waved Livermore away from

his “Not my problem!” Immigration window officials to Dr. G’s more friendly Immigration official’s

window and was told to be tranquil, not to try to perplex the harried bureaucrats

with his flustering, trying to circumvent a requirement he had screwed up and watch how some government workers could be friendly and

helpful, not a hindrance. An hour later Dr. G's Immigration officer had provided

a solution not required by her. An unofficial Internet connection was found and unofficially used to pay for the fee and the printed Reciprocity Fee documents allowed the pair

and their motorcycles to enter Argentina.

Rene Dhenin, pictured

above on his Kawasaki KLR650, from Ridgway, Colorado, joined the “RTW Motorcycle

Rally Adventure Team” in Bariloche, Argentina. Celebratory fist bumping after having

successfully reaching Ushuaia and the southernmost point on the continent of

South America, Dhenin did not realize until the bill came for the celebration dinner

that his joining the team meant as a newbie he was responsible for paying

because he jumped the Start in Bogota, leaving before the Clancy banner waved

off the entrants for the official beginning. It was a large bill that included

some pricey Argentine squeezing of grapes ordered by Livermore.

Americanization could not easily be shaken off as the pair

entered Spanish Argentina. One was lusting for farm style bacon and eggs for

his breakfast, pooh-poohing the fruit, cereal, toast, pastries, juices and rich

coffee offered each morning as part of their hotel charge. Someone could almost imagine him including the words

“Denny’s Grand Slam, Denny’s Grand Slam, Denny’s Grand Slam” during his evening

ablutions and prayers, if not mumbled while dreaming.

Pictured is a typical

breakfast offering at a moderately priced Argentine hotel. While one of the pair prepared his own coffee

in his hotel room with the portable hot water maker, cup and coffee he carried, the other

took advantage of the large breakfast selection, powered up for the morning and

before leaving made two sandwiches from the ham, cheese and fresh bread which

he pocketed and snacked on during the day.

Another noted difference upon entering Argentina was the addition

of a bidet in the bathrooms of hotels, motels and hostels. A bidet was not a toilet appliance either had

seen growing up in Indiana, Montana or when passing through Kansas. Noting the unique fixture, Dr. G said to the Livermore at dinner one evening, “You see the bidet in your bathroom?”

“Bid what?” replied Livermore.

“That porcelain apparatus next to the toilet with the

handles and drain, the one mounted on the floor.”

“Oh yeah, I used it last night and this morning. Kind of

like what is next to the chair in the dentist’s office, only there you can’t

adjust the water temperature or power flow. First time I used it I nearly blew

off my glasses, gave my face a good washing. ”

A Frenchman at the next table, overhearing the American's

conversation, leaned over and injected himself into the pair’s conversation by

haughtily saying, “It’s pronounced “bit day” and is for washing your genital,

perineal areas and inner buttocks.”

“Oui,” said one of the Americanized pair, smiling at his

worldly display of the French language and global hygienic knowledge.

The other, wanting not to appear too much from Kansas, said,

“Just cuz I’ve been using it for washing my mouth out after brushing my teeth

doesn’t mean I don’t know what perineal means, Mr. Pepe Le Pew.”

This rather unique

bidet/toilet combination is what gave the one of the farm grown Americans in

Argentina grounds for liking it to the mouth wash mechanisms in his dentist’s

office, and which nearly blew off his glasses when he first applied farm boy

strength to adjusting the water flow and temperature, while bending over face down

to see the knobs close up.

The most common motorcycles seen as Livermore and Dr. G

entered Argentina’s famed Patagonia area were BMWs. Whether in a group on a fully

supported and guided tour or roaming alone, one or two-up, the Bavarian

motorcycles were seemingly the brand of choice. Dr. G, a certified BMW mechanic and Adventure

Editor-at-Large for Kawasaki’s ACCELERATE magazine, admitted to being an

agnostic when asked which brand of motorcycle was his favorite for adventure

touring or travel. Livermore, a collector

of Honda GL650s, admitted to his persuasion, and particularly so for the turbo

charged 1983 models. Both would often engage in conversation with other motorcycle

travelers regarding their choice of motorcycle and tires for the often

difficult roads of Argentina.

An Argentine street

dog sniffed around Dr. G’s and Livermore’s old (1983) Honda motorcycles while

they were trading road stories and motorcycle preferences with a BMW

owner. Livermore said, “You meet the

nicest people on a Honda.” A certain amount of German quality, and paid high price,

was being proffered by the BMW owner, until the Spanish dog chose the Bavarian

rear wheel to water as pictured here.

Dr. G said, as the dog wandered away, “Well, I guess that tells us what

one inhabitant of Argentina thinks about what is expensively marketed as ‘the ultimate

riding machine.’”

With no schedule other than a due date for their next scheduled pit stop,

Livermore and Dr. G were free to pursue routes and travel roads seldom taken by

foreign motorcyclists through southern Argentina.

90% of the motorcyclists they met between Buenos Aires and Patagonia were

either coming or going to Ushuaia. Dr. G

had been there twice before and recent reports of his scratched name and date

still being visible on the back of a certain national park sign where he carved

them in 1997 meant he needed not to make his mark again. Livermore, after enduring several days of

cold and Casper, Wyoming-like winds across the pampas of Patagonia, wanted to vector northward towards bikini wearing sun bathers, a suggestion that

passed by a vote of 1-0.

A surprise below the

Rio Negro in Patagonia was the lack of gasoline, resulting in several instances

long lines. While the Honda GL650s would

run equally well on all octane levels of gas at the stations, Dr. G and

Livermore sometimes had to wait for an hour or longer for their 4-5 gallons as

jumping ahead in the line for motorcycles was not accepted. A road rumor was that further south a crashed

tanker truck had left several gas stations empty with cars and motorcycles waiting

several days for a replacement tanker to arrive, waiting where there was no

lodging, no restaurants, and no bikini wearing sun bathers. Dr. G said, "I'm for it, sounds like adventure." Livermore said, "Nah, I'm for adventure in a Marriott or Hilton hotel in Buenos Aires."

The last travel bump in the road around Argentina was within

a mile of the pair’s targeted hotel in Buenos Aires. Livermore had

reserved rooms with safe motorcycle parking at a hotel that was, as he stated, "across the

street from a Starbucks." Dr. G failed to make note of the

hotel name or address and, as they approached a multi-level highway interchange, the

reservation-maker, following behind his non-knowing pal, vectored off to the

right while Dr. G went left.

Two hours later the frustrated, tired,

hot, and no-GPS or telephone carrying Dr. G finally found the

right Starbucks. He did so by riding in

wider ranging circles through the lower bowels of Buenos Aires, asking taxi cab

drivers and hoteliers where the nearest Starbucks was, while learning there

were several of the Americanized coffee cafes in the greater area of 13,000,000

people in Buenos Aires. His moral to the afternoon of wandering urban adventure

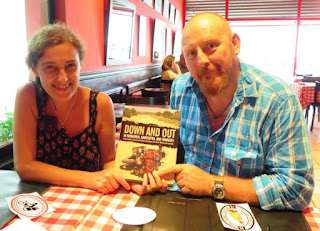

riding, looking for his Americanized coffee junkie riding pal was, “You can take some men

out of America but you can’t take Americanization out of the man, or his addiction to Toasted White Chocolate Mocha With Soy Milk."

A surprise visit from

Sandra and Javier Kaper, motorcycle gurus and shipping experts based in Buenos

Aires, was an enjoyable meeting for Dr. G.

He had met the pair 10 years earlier on his second journey through South

America and been in contact with them, often through third parties, some even sending

him photographs of motorcycle parts he had left in Buenos Aires at the motorcycle

shop Javier then operated. Dr. G

autographed a copy of his latest best-selling book, DOWN AND OUT IN PATAGONIA,

KAMCHATKA, AND TIMBUKTU http://bit.ly/1Q1hZ2O and the trio caught up on ten years of

their lives, road tales and traded or dispelled gossip.

Several times in Argentina Dr. G was misidentified as Ozzy

Osbourne. Once was when an American tourist said, “Has anyone ever told you that

you look like Ozzy Osbourne?” A second

time was when a passerby in their hotel pointed at Dr. G and said to her husband, “Look,

there’s Ozzy Osbourne!” A third time, an attractive waitress in a restaurant asked Dr.

G, “Are you a rock star? Ozzy Osbourne?”

Dr. G, not one to pass on a compliment, especially from a

pretty lady, rose to the bait and replied, “I’m no rock star, I’m Ozzy’s

doppelganger. When Ozzy is sick, or too far out in space to go on stage, I take

his place. He’s the rock star; I’m just the back-up guy.”

The waitress said, “That’s soooo cool, and you’re so

humble. That’s very nice of you. Would you give me your autograph?”

Dr. G, author of the book MOTORCYCLE SEX, thought for a few

seconds, and said in the spirit of being Ozzy and the published authority on

the topic of his book , “OK, but only if I can write the autograph on your

************.”

The waitress blushed, then said “OK,” and lifted up her tank top and supporting garment to bare skin where

Dr. G wrote with a flourish, while using both hands, OZZY2.

Photo of Argentina

Ozzy Osbourne doppelganger. So wrong, but soooo funny.

Both 33 year-old Honda

motorcycles and young-at-heart drivers completed the second stage of The Great

Around The World Motorcycle Adventure Rally in Argentina. Livermore, here

displaying the banner from Ireland and carried on the The Clancy Centenary

Ride, was already making a check-list of what he wanted to pack and carry for

their next stage, Africa. Dr. G, having

been to Africa several times before, dryly said of the what Livermore could

expect compared to South America, “I believe when Stanley finally found

Livingstone in 1871, sitting on a commode, he not only said, ‘Dr. Livingstone,

I presume?’ but added, ‘Is it true you carried that toilet and seat the entire

way?’”